Every second, our immune system makes thousands of life-saving decisions-whom to attack, what to protect, and when to stop. This year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine honors three remarkable scientists who revealed how that delicate control works.

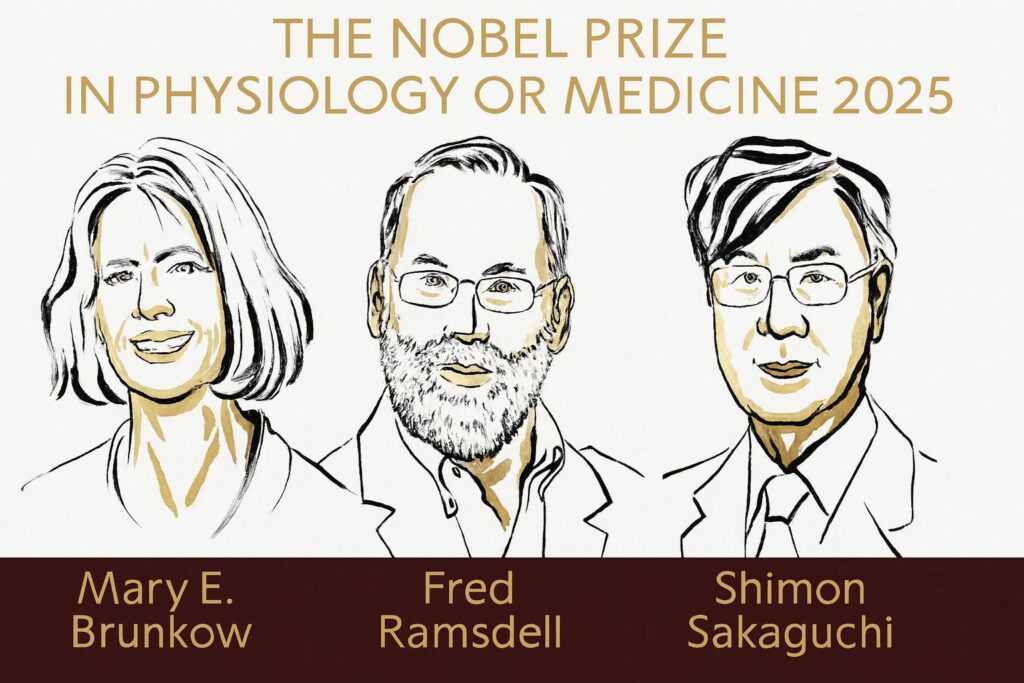

The 2025 Nobel Prize has been awarded jointly to Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell, and Shimon Sakaguchi for their discoveries concerning peripheral immune tolerance. Their collective work explains how the immune system restrains itself from attacking the body’s own tissues and why that control sometimes fails, leading to autoimmune diseases.

Understanding the immune paradox

The immune system is an evolutionary masterpiece strong enough to destroy viruses and bacteria, yet precise enough to leave our own cells unharmed. For decades, immunologists believed that this precision was set during the early life of immune cells in the thymus, a process known as central tolerance.

But that wasn’t the full story. Even with this built-in filter, some “self-reactive” T cells still escaped into circulation. So why didn’t they cause disease in everyone?

This mystery hinted at a second checkpoint, a dynamic mechanism that controls the immune system outside the thymus. That external control system is called peripheral immune tolerance, and discovering how it works is what brought Brunkow, Ramsdell, and Sakaguchi to the Nobel stage.

Shimon Sakaguchi: The pioneer of regulatory T cells

In the 1980s, while working at the Aichi Cancer Center in Nagoya, Shimon Sakaguchi began revisiting an unpopular idea “suppressor T cells.” The concept had been largely dismissed, but Sakaguchi noticed something striking: mice that lacked a thymus developed rampant autoimmune diseases, and transferring certain T cells could restore balance.

After years of careful work, he identified a subset of T cells that carried two key surface markers CD4 and CD25. These cells did not activate the immune system; instead, they calmed it down. In 1995, Sakaguchi published the landmark study describing these cells, naming them regulatory T cells (Tregs).

Tregs were the immune system’s internal peacekeepers essential for preventing self-destruction. This discovery was initially met with skepticism, but genetic evidence would soon confirm it.

Mary E. Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell: Finding the genetic switch

On the other side of the world, in a biotechnology laboratory in Washington state, Mary E. Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell were studying a mysterious mouse strain known as scurfy. The male mice were born sickly, with inflamed organs and an overactive immune system.

The two researchers set out to find the exact gene responsible. In the 1990s, before fast genome sequencing existed, this was like searching for a single misspelled word in an entire library. After years of persistence, they narrowed it down to one region on the X chromosome and discovered a previously unknown gene—Foxp3.

Their 2001 paper in Nature Genetics revealed that mutations in Foxp3 cause fatal autoimmunity in mice. Soon after, they confirmed that mutations in the human equivalent, FOXP3, lead to a devastating rare disease in children called IPEX syndrome (Immune dysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, Enteropathy, X-linked).

FOXP3 turned out to be the master regulator the genetic switch that programs T cells to become regulatory T cells. Without it, the immune system cannot distinguish between self and non-self, leading to uncontrolled inflammation.

How these discoveries fit together

Sakaguchi’s identification of regulatory T cells provided the cellular foundation, while Brunkow and Ramsdell’s discovery of FOXP3 supplied the molecular key. Together, their work created a complete picture of immune tolerance.

In 2003, Sakaguchi and colleagues confirmed that FOXP3 directly controls the development and function of Tregs. This linked all three discoveries into one elegant mechanism:

- Tregs, defined by CD4⁺, CD25⁺, and FOXP3⁺, suppress overactive immune cells.

- When FOXP3 is defective or missing, Tregs fail to form, leading to autoimmune disease.

- Restoring or enhancing Tregs can restore balance and prevent tissue damage.

This mechanism, called peripheral immune tolerance, now underpins a major branch of immunology and medicine.

From discovery to therapy

The impact of these discoveries reaches far beyond the laboratory. Researchers are now designing therapies that fine-tune the immune balance rather than simply suppress it.

- Autoimmune diseases: Scientists are testing low-dose interleukin-2 (IL-2) and engineered Treg cell therapies to treat conditions like type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and lupus by strengthening immune tolerance.

- Transplantation: Treg-based strategies aim to help patients accept new organs without lifelong immunosuppressive drugs.

- Cancer: Some tumors exploit Tregs to shield themselves from attack. By temporarily blocking these cells, immunotherapies may help the immune system better target cancer.

The same biological insight how to turn tolerance up or down is being used to solve problems that once seemed unrelated.

The laureates behind the breakthroughs

- Mary E. Brunkow (born 1961, USA) earned her Ph.D. from Princeton University and now works at the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle. Her careful genetic mapping of the scurfy mouse was a masterclass in persistence during a pre-genomic era.

- Fred Ramsdell (born 1960, Illinois, USA) completed his Ph.D. at UCLA and is currently Chief Scientific Officer at Sonoma Biotherapeutics in San Francisco, where he focuses on developing Treg-based therapies for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.

- Shimon Sakaguchi (born 1951, Japan) earned both his M.D. and Ph.D. from Kyoto University and serves as Distinguished Professor at Osaka University’s Immunology Frontier Research Center. His discovery of regulatory T cells changed the course of modern immunology.

The future of immune tolerance

Today, researchers are building upon these findings using tools that didn’t exist in the 1990s single-cell sequencing, CRISPR editing, and artificial intelligence. These technologies help scientists map FOXP3’s gene network, track Treg dynamics in real time, and even design personalized immunotherapies.

AI models are now being trained to predict when tolerance will fail helping doctors anticipate autoimmune flare-ups or transplant rejection before symptoms appear. The field that began with three scientists’ curiosity has become a global effort to reprogram immunity safely.

A story of persistence and collaboration

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Medicine is more than a recognition of individual achievements it’s a celebration of collaboration across continents and generations. Sakaguchi’s fundamental insight, Brunkow’s technical perseverance, and Ramsdell’s translational vision show how discovery science connects to real human benefit.

Their work reminds us that progress often starts with a single, unpopular question and the courage to keep asking it.

References

- Sakaguchi S., Sakaguchi N., Asano M., Itoh M., Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor α-chains (CD25). J. Immunol. 1995.

- Brunkow M.E., Jeffery E.W., Hjerrild K.A. et al. Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat. Genet. 2001.

- Hori S., Nomura T., Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003.

- Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet. Popular Information: They understood how the immune system is kept in check. 2025.

Stay tuned for more updates, discoveries, and insights from the world of science.

Follow BioCareersHub for inspiring stories and the latest in research and innovation.