In the age of convenience, the food on our plates often comes wrapped in plastic, with ingredient lists that look more like chemistry experiments than recipes. From pre-packaged sandwiches and flavored yogurts to colorful cereals and energy drinks, ultra-processed foods (UPFs) have silently become a cornerstone of modern diets.

But what if we told you your body — not your memory — is the most honest record keeper of what you eat?

A landmark study published in PLOS Medicine (Abar et al., 2025) and featured in Nature (Mallapaty, 2025) has introduced a game-changing method to objectively track how much UPF a person consumes, using blood and urine samples. The implications go far beyond nutrition—they touch on chronic disease risks, food policy, and even the future of personalized health.

Why Traditional Food Tracking Falls Short

Most studies that link diet to disease rely on self-reported food intake, which is notoriously flawed. People forget, underestimate, or misreport their meals. Did you really eat only one cookie? Was that store-bought lasagna ultra-processed or homemade?

The limitations of recall-based studies have long cast shadows over nutrition research. Enter a better approach: metabolomics — the study of small molecules (metabolites) left behind in our bodies after we metabolize food.

The Study: A Metabolic Mirror of What We Eat

Dr. Erikka Loftfield and her team at the US National Cancer Institute analyzed blood and urine samples from 718 healthy adults aged 50–74. Each person provided samples twice, six months apart, and completed up to six 24-hour dietary recall surveys over the year.

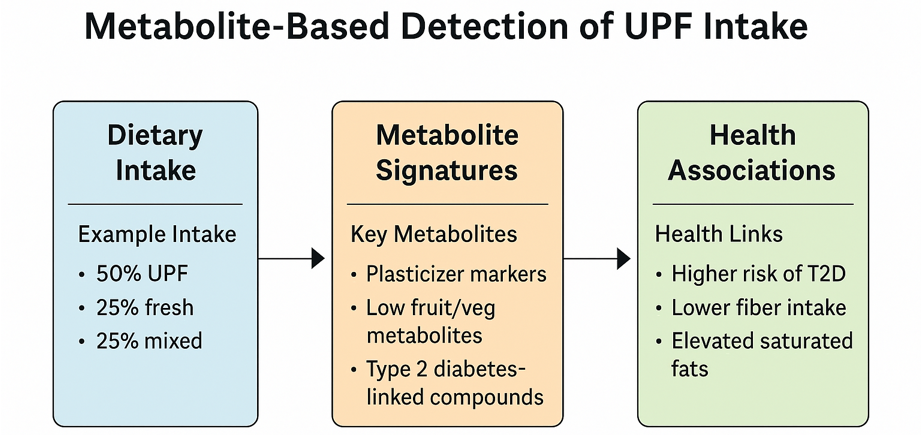

But instead of just trusting what participants said, researchers used machine learning to match over 1,000 identified metabolites with dietary patterns and categorize foods based on their level of processing.

What the Metabolites Revealed

On average, 50% of daily calories came from UPFs — but the range spanned from just 12% to 82%. Those who consumed more UPFs:

- Had higher levels of metabolites associated with type 2 diabetes

- Showed evidence of chemicals from food packaging in their urine

- Had fewer markers from fruits and vegetables, indicating low nutrient intake

This means your urine can tell whether you’re eating whole grains or ultra-processed crackers — and potentially whether you’re at risk of future disease.

UPF Consumption vs Metabolic Markers

| UPF % in Diet | Added Sugars | Fiber | Fruit/Veg Markers | Diabetes Risk Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (12–25%) | Low | High | High | Low |

| Medium (40–60%) | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| High (75–82%) | High | Low | Very Low | High |

The Double-Test: Controlled Trial Verification

To test if this detection method could work under controlled conditions, researchers ran a randomized crossover diet study with 20 individuals aged 18–50. Each person followed two types of diets for two weeks each:

- UPF-rich diet

- Whole-food diet

The results were crystal clear: blood and urine samples could accurately distinguish between the diets, validating the metabolite scoring system.

Even packaging-related molecules showed up in the samples of those on ultra-processed diets.

Why This Matters in 2025

We live in a world where avoiding ultra-processed foods is harder than it seems. Most industrial food systems are designed for scale, cost-efficiency, and shelf life, not for nutritional integrity.

Dr. Oliver Robinson from Imperial College London aptly said,

“We’re sort of trapped in this industrial food-production system.”

Even those trying to eat healthy may unknowingly consume hidden UPFs, masked by labels like “low fat” or “fortified with vitamins.”

So what exactly is harmful — the processing itself, the additives, the packaging? Or is it the absence of real, whole nutrients that matters most?

Loftfield’s research lays the foundation to finally answer that question — not with speculation, but with biological evidence.

From Self-Reports to Biomarkers: A Paradigm Shift

This metabolite-based method opens the door for real-time, personalized nutrition science. Instead of asking people what they ate, researchers and clinicians can now look at their biochemistry.

This shift could revolutionize how we study diet and disease, personalize dietary advice, and even inform food policies or food labeling systems. Imagine walking into a clinic and getting a blood test that tells you not just your cholesterol — but how much junk food your body has processed.

Final Thoughts: Your Body Is Telling You the Truth

We now know that you can lie to yourself, but your metabolites won’t. This study doesn’t aim to shame anyone into avoiding convenience. Rather, it offers a powerful new lens to help us understand how the invisible chemical signals in our body tell the story of what we consume.

As the science matures, this might be the future of health assessments — and possibly even the future of food accountability.

References

- Abar, L. et al. (2025). PLOS Medicine, 22, e1004560.

- Mallapaty, S. (2025). Nature News. “How much ultra-processed food do you eat? Blood and urine record it.”

- Beslay, M. et al. (2020). PLOS Med, 17, e1003256.

- Cordova, R. et al. (2023). Lancet Reg Health Eur, 35, 100771.

Interested in more such science-backed stories and career insights?

Visit us at www.BioCareersHub.com — where science meets career.

Don’t forget to follow us on Facebook for weekly posts, research guides, and opportunity alerts!